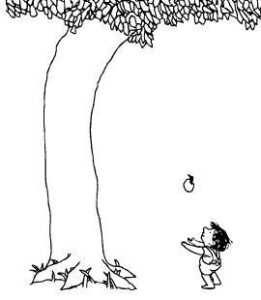

Shel Silverstein’s children’s book, ‘The Giving Tree’1 has sold many millions of copies since 1964, but has been dogged by controversy ever since it first appeared. It is a tale of the relationship between the Tree and a boy, always able to magically communicate with one another, as the boy moves from childhood to old age. The boy comes and goes, and seems to lead a troubled life; the constant is how the Tree remains available for whenever the ‘boy’ (as he is always called) returns, always offering what she can to meet the boy’s wishes, and offer some solution, relief or sustenance.

Shel Silverstein’s children’s book, ‘The Giving Tree’1 has sold many millions of copies since 1964, but has been dogged by controversy ever since it first appeared. It is a tale of the relationship between the Tree and a boy, always able to magically communicate with one another, as the boy moves from childhood to old age. The boy comes and goes, and seems to lead a troubled life; the constant is how the Tree remains available for whenever the ‘boy’ (as he is always called) returns, always offering what she can to meet the boy’s wishes, and offer some solution, relief or sustenance.

I was troubled by the story of the Giving Tree. On the plus side, and on the face of it, it seems to be a story of the unconditional love from the Tree. On the minus side, the boy seems to go through life with a growing sense of loneliness, disillusion, selfishness, and meaninglessness; and the result is not sustainability of the Tree, but its depletion, exhaustion and ultimate destruction. In an interview (1964) published by the Chicago Tribune, Silverstein himself said that he managed to persuade the publisher to keep the sad ending “because life, you know, has pretty sad endings. You don’t have to laugh it up even if most of my stuff is humorous.”

In 1995, First Things (Richard John Neuhaus, ed.) published a symposium of writings on ‘The Giving Tree’. William F May (Professor of Ethics) wrote, this is a story where “a compulsive giver fatally bonds with a predatory taker. A kind of co-dependency takes hold, with lethal consequences for them both.” Mary Ann Glendon (Professor of Law) described it as “a period piece-a nursery tale for the ‘me’ generation, a primer of narcissism, a catechism of exploitation”. When the Tree’s trunk is finally cut down to be made into a boat (so that only a stump is left), we read, “The Tree was happy …. but not really.” That for me, is telling. It is the first hint that something is not right in the relationship. We find out in the next ‘movement’ in the story; it turns out that the Tree is no longer able to bear fruit, has no branches to swing and play on, and no trunk to climb – all the things that the ‘boy’ could do with the Tree before. Timothy Fuller (Dean of Colorado College) wrote of his concerns about the lack of purpose, redemption, maturity, responsibility, insight or learning, repentance, or character, and the notes of naivety, exploitation, injustice, sentimentality, sadness and despair. Should we be like the Tree? I agree with Jean Bethke Elshtain (Professor of Social and Political Ethics), who wrote: “I do not aspire to stumpdom”. As an approach to being human and in relationship, the Tree is not a healthy model. And the ‘boy, even when an old man, is still referred to as the ‘boy’, suggesting he has not learned anything from the Tree about what maturity might be.

Was ‘The Giving Tree’ Silverstein’s final philosophy on life, giving, relationship and ethics? Absolutely not. He wrote the book in 1964, but, for example, in 1979, he wrote a book called ‘Different Dances’ (satirically commenting on “the social calamities and absurdities of the adult world”), in which he plays with the idea that the 10 Commandments were originally 20; amongst those Moses supposedly left discarded on the mountain top (because the tablets were too heavy for him to carry all of the ‘originals’) were “thou shalt remember every day to keep it holy” and “thou shalt not destroy the earth before its time”.

As I spent more time with Silverstein’s story, I wondered what might come of the thought-experiment of juxtaposing it next to the Jewish teaching that the Torah is a ‘tree of life’. (Silverstein was Jewish, but, as far as I can ascertain, was not religious, and I cannot find any record of him making this connection.)

In Proverbs 3:18 we read: “She is a tree of life to those who grasp her, and whoever holds on to her is happy.” (JPS translation) We first learn of the idea of a tree of life eitz chayiim in Genesis 3:22. The Talmudic Rabbis took the Proverbs verse about the tree of life to refer to the Torah, and how we should relate to it. What can we learn by looking at the shoresh (root) and associations of some of the Hebrew words?

- The word for ‘life’ is chayah, which implies sustenance, and even the renewal or restoration of life.

- The word for ‘grasp’ in the Hebrew is related to chazak, meaning ‘strong’ – we must grasp strongly to the Torah if it is to sustain us.

- The root word for ‘holds on’ is tamak, which, means not just ‘hold’, but alternatively, ‘support’. Perhaps we can learn from this that it is not enough just to hold on to the Torah. We must actively, and reciprocally, support it, which means living it, as well as preserving and teaching it.

- Finally, the word for ‘happy’ is ashar. This is more than just contentment, elation, or even ‘blessed’. It comes from the root meaning ‘to go straight’, ‘to advance’, being ‘honest’ and ‘proper’. Perhaps this is similar to transcending suffering, and living the Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path of right view, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. This is the meaning of ashar in ashrei ha’am (happy are the people), and yashar el, one interpretation of Yisrael, the people who go ‘straight to God’.

So, here is an expanded translation of Proverbs 3:18:

“The Torah is a source of life-giving sustenance, reviving those who make a strong connection to her and hold on to her; and whoever goes beyond just holding on to Torah, and supports her (through how they live, preserve and teach her) will be upright, blessed, and move forward honestly and in the right way.”

What happens to Silverstein’s text when it is studied as an (albeit unintentional) allegory? As a youngster, the boy makes crowns from the leaves of the tree and pretends to be ‘king of the forest’. When he is very young, he is very close to his pure, spiritual state; in kabbalah, on the Tree of Life, this is keter the ‘crown’. The mystical poet Thomas Traherne (17th century) wrote of the child’s special spiritual condition: “My knowledge was Divine”. The boy eats the Tree’s apples; he is taught the most appealing parts of Torah, even taught it while tasting honey (the apples of the Giving Tree) so that he grows to love her. He plays ‘hide-and-go-seek’ with the Tree; when young, he may hide from the more serious teachings of Torah, but can be gently sought out and brought to them. And he sleeps in the Tree’s shade, learning to say the bedtime Shema (texts from Torah) so that he sleeps in its embrace.

As an adolescent the boy thinks himself “too big to climb and play” with the Tree. He resists, not wanting to spend time with Torah, or ‘climb’ to greater understanding of her. He wants to become successful and make money. Like the Tree, the Torah can offer him ‘apples’, wisdom in how to do even these things.

The adult ‘boy’ says he is “too busy” to play with the Tree, and wants to build a house. He chops off the branches of the Tree; later in the story this means he can no longer play in the branches, or receive any more fruit. He can learns from the Torah how to make a good home and family life. But his mistake is to diminish the Tree, taking from the Torah only what is convenient to him (the ‘branches’), forgetting the Source and fuller context from which the wisdom comes, and sabotaging his access to the full Torah.

In later life, the boy is “too old and sad to play”, saying “life is not fun”. He wants something from the Tree that will make it all better (a boat to sail away in). By this stage in the relationship, he is unhappily trying to derive something from Torah, without having committed to a learning, nourishing, reciprocal relationship with her. He gets the trunk for the boat – he returns to the core teachings of Torah – but no longer derives any happiness, because he has lost sight of what happiness is. As an old man his teeth are too weak to eat apples, he is too old to swing on the branches and too tired to climb. He has failed to give time to creating a healthy relationship with the Torah that might sustain him in later years. At the end of his life, he sits down on the remaining stump of the Tree. Perhaps this is his final Shema on his deathbed.

The boy’s life might have been so different had he established a greater sense of reciprocity in his relationship to the Tree (Torah). Throughout the story, the Tree is said to be ‘happy’ when it finds itself able to give something to the boy – the Tree knows many moments of joy, and in each encounter, encourages the boy once more to play. But joy is something that, as a child, the boy knew, but did nothing in later life to retain and nurture. As a child, his spirit naturally wore a ‘crown’ of joy. We learn from the Ethics of the Ancestors (lit. ‘Fathers’) about the ‘crown of Torah’ (Pirkei Avot 4:13). But, ultimately, this crown must be earned through a lifetime of study and right living, as Maimonides taught in the Mishneh Torah. We are also taught:

“One who does not increase, diminishes. One who does not learn is deserving of death. And one who makes personal use of the crown of Torah shall perish.” (Pirkei Avot 1:13)

“Do not make the Torah a crown to magnify yourself with, or a spade with which to dig. So would Hillel say: one who makes personal use of the crown of Torah shall perish. Hence, one who benefits himself from the words of Torah, removes his life from the world.” (Pirkei Avot 4:5)

Reading Silverstein’s book as an unintentional allegory for our relationship to Torah, I see it as a cautionary tale. The Torah will always give us something, but we can distort our relationship with her and lose out in the long term. The Torah is more than just a Giving Tree. She is a Living Tree. She can sustain us, but we, in turn, must find out what it means to sustain her also. We must let the Torah live in our hearts, and then we will discover her true life-giving force, and her beauty, and. In the words of William Butler Yeats (‘The Two Trees’ 1893):

“Beloved, gaze in thine own heart,

The holy tree is growing there;

From joy the holy branches start,

And all the trembling flowers they bear.”

Notes

[1] Listen to Shel Silverstein narrate it on a 1973 animated version on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1TZCP6OqRlE