What weight should we give to the voices from the past? After all, we don’t do exactly what was done in the past, not least because we cannot know for sure what was done, but also because conscience, common sense, or new knowledge to which the Rabbis did not have access persuade us to do otherwise. Yet so much of what we know, believe and do in Jewish life is based on inherited traditions – without the Jewish past, there is no meaningful Jewish present. I find myself sometimes oppressed, and sometimes liberated by Judaism.

What weight should we give to the voices from the past? After all, we don’t do exactly what was done in the past, not least because we cannot know for sure what was done, but also because conscience, common sense, or new knowledge to which the Rabbis did not have access persuade us to do otherwise. Yet so much of what we know, believe and do in Jewish life is based on inherited traditions – without the Jewish past, there is no meaningful Jewish present. I find myself sometimes oppressed, and sometimes liberated by Judaism.

Without Talmud1

Tradition is nothing.

Without Tradition

There is no Judaism.2

Ancient wisdom nurtures3,

Custom teaches,4

Discipline liberates,

Ritual transforms.Wisdom honours both pastand present.6Discipline can imprison,Custom lack compassion.7Ritual made freshrenews the soul.8Without TraditionWithout conscienceI am nothing.11Without you,12Breath within the Breath13,Tradition and conscienceare nothing.14Hineni – here I am.15

Commentary

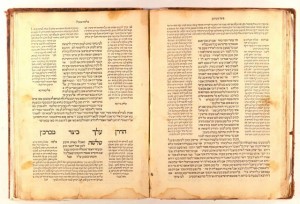

[1] תלמוד (teaching / instruction / learning) The Talmud is a two part body of work evolved by the Rabbis, the first part being the Mishnah(200 CE), and the second, the Gemara (500 CE), which includes discussion of the Mishnah as well as other related writings; the Gemara is the basis for all the codes of Rabbinic law. The writings are traditionally categorized as either aggadah (discussion, analysis, story etc) orhalachah (Jewish law and practice). The Talmud represents the foundation of the tradition of Rabbinic teaching and authority. It is in two versions: Jerusalem Talmud (c. 400 BCE) and Babylonian Talmud (c.500 BCE).

[2] In the opening verse of Pirkei Avot (‘Ethics of the Fathers’, an important 2nd century text of the Talmud), the claim is made that the Rabbis have a direct lineage of authority reaching back through the prophets, the elders, and Joshua to Moses himself. As Shapiro (Ethics of the Sages: Pirkei Avot annotated and explained, Skylight Illuminations, USA, 2006, xi) writes, “without the first sentence of Pirkei Avot, Judaism disappears.” We could surrender to the centuries-old lineage of the Rabbis, who taught that all of the written Torah was torah min ha-shamayim, ‘from heaven’, divinely inspired, and therefore not to be questioned or overturned. The 18th century Chabad-Lubavitch movement has countered arguments that the Rabbis were simply humans putting their own interpretations and political spin on Torah andTanakh text. Their defence of the decisions and directives made by the Rabbis is that there were prophets within the Men of the Great Assembly (the people traditionally believed to bridge the chronological gap between the Torah and the Rabbis) who ensured that liturgical and halachic decisions were guided by the Divine.

[3] John Rayner (1998b), one of Progressive Judaism’s leading lights, has clearly and persuasively argued that to dismiss the painstaking work of the Rabbis would be a grave mistake, not just for Jewish people, but for anyone seriously interested in leading an ethical life, or constructing and maintaining an ethical framework for human relationships, or relationships between humans and their environment. For the Bible and the Rabbinic response to it represent an extraordinary, illuminating and detailed attempt at presenting a set of teachings on how to do what is good. (Rayner, John (1998b) Jewish Religious Law: a progressive perspective, Berghahn, Oxford)

[4] Cultural authority – in Judaism, minhag – can exist in a small, local community, across a larger geographical area, a whole denomination, historical period, or religion (for example, the Shema having primacy across all of Judaism.) The character Tevye in ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ says: “Traditions, traditions. Without our traditions, our lives would be as shaky as… as… as a fiddler on the roof! … Because of our traditions, we’ve kept our balance for many, many years. Here in Anatevka, we have traditions for everything… How to sleep, how to eat… how to work… how to wear clothes. For instance, we always keep our heads covered, and always wear a little prayer shawl that shows our constant devotion to God. You may ask, “How did this tradition get started?” I’ll tell you! [pause] I don’t know. But it’s a tradition… and because of our traditions… Every one of us knows who he is and what God expects him to do.” [Bock, Jerry (music) and Harnick, Sheldon (lyrics) (1964) Fiddler on the Roof, musical based on the Yiddish book of tales by Aleichem, Sholem (1894) Tevye and his daughters]

[5] The Shema itself warns us: “Beware lest your heart/mind be deceived, and you turn and serve other gods and worship them.” (Deut 11:16) As a prominent voice of Liberal Judaism, John Rayner has warned that we make a serious mistake if we were to regard the Torah, or the Rabbis’ centuries-old halachah (Rabbinic law) and aggadah (storied teaching) as ‘from heaven’, and therefore the final word on all matters biblical, ethical or spiritual: “We liberals would wish to be worshippers of God, not of the Bible; and we believe that to use our God-given critical intelligence to understand the Bible, and the subsequent literature, is the best chance we have of arriving at a true understanding of what God is and requires of us.” (Rayner, 1998a, p.57). Rayner, John (1998a) A Jewish Understanding of the World, Berghahn, Oxford

[6] Judaism must continue to evolve for three reasons: a) to address contemporary needs and outlook 2) because growth and change are fundamental to life, and to resist change is to resist life 3) the requirement to use our responsive creativity to evolve is laid down in the Bible, in the commandment to Adam and Eve (Gen. 1:28), and later to Noah (Gen. 9:1) pru ervu “be fruitful.”

[7] At its best, minhag celebrates and sustains the very essence and texture of Judaism, and at its worst, it can be invoked to defend bigotry and irrationality, and stifle innovation, or enlightened, compassionate response. Minhag is a crucial part of Jewish unity and continuity. And yet, the fact that something has been done by many Jewish people, across all denominations (including even secular Jewish people), over many years, does not make it morally right, or necessarily appropriate at all times and in all places. Another cherished value of Judaism is not to let a minority suffer at the hands of a majority. Invoking the supremacy of minhag – and therefore the weight of numbers – risks oppressing a (current) minority that conscientiously objects but who in every other respect are committed to Judaism and the Jewish people. Requirements made by both halachah and minhag have to survive the Jewish tests of justice and mercy.

[8] “Since the ancient Scriptures carried with them the command for constant study, they could not become a dead weight; they implied the adaptation of the materials of the past to the present. Even the forces of authority of Jewish religious life had to acknowledge and accept the tendency of constant reinterpretation. Thus the authority did not lead to dogmatism. The mental struggle to discover the true idea, the true command, the true law (a hundred-sided question without a final answer) always began anew. The Bible remained the Bible, the Talmud came after it, and after the Talmud came religious philosophy, and after that came mysticism, and so it went on and on. Judaism never became a completed entity; no period of its development could become its totality. The old revelation ever becomes a new revelation: Judaism experiences a continuous renaissance.” [Baeck, Leo (1948) The Essence of Judaism, Shocken Books, New York]

[9] It makes no sense to want to call myself Jewish unless I am prepared to make a connection with Jewish history. And the opening prayer of the Shemoneh Esreh (18 Blessings / Amidah / ‘Standing Prayer’), the centerpiece of the Jewish morning service designed by the Rabbis, does just this, acknowledging that Jewish people stand in the procession from the avot ‘the ancestors’ looking back to where they have come from. Jewish people learn from the historical-mythical past, not just the glories and errors in the stories and legends of Biblical figures and peoples, but also the breakthroughs and misjudgments of succeeding generations up to the present day. It would be arrogance and folly to ignore how the past can guide us, just as it would be arrogance and folly to insist the past should govern us in the present or the future.

[10] What persuades me to be Jewish, to live Jewishly, is that being Jewish gives me meaning; the stories, traditions, liturgy and teachings, spirit of learning and dialogue, and way of approaching relationship, community and life itself, encoded in Jewish psyche and culture inspire me, and awaken my ethical sensibilities. Jewish story, Jewish community, Jewish ethics and tzedakah, Jewish liturgy, and a Jewish religious outlook provide an intellectual, emotional and spiritual rudder through my physical existence.

[11] Halachah and minhag must be reassessed in the light of modern sensibilities, modern scientific understandings that were unavailable in Biblical and Talmudic times, and also withstand the tests of gender equality, intellectual rigour and personal conscience.

[12] For me, this is the transformative moment in this poem, the shift into direct dialogue.

[13] This phrase comes from a poem by the 15th century Indian mystic Kabir: “O servant, where dost thou seek Me? Lo! I am beside thee. I am neither in temple nor in mosque: I am neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash: Neither am I in rites and ceremonies, nor in Yoga and renunciation. If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see Me: thou shalt meet Me in a moment of time. Kabir says, ‘O Sadhu! God is the breath of all breath.’” Jewish mysticism is steeped in the symbolism of the soul as breath (ruach, neshamah), and the breath relationship between humankind and the Creator.

[14] There is a danger that we remain exclusively secular, and that we swing between honouring the wisdom of others, and turning to our own conscience and intuition, as though these are our only sources of authentic ‘knowing’. The reason we are commanded to “love the Lord our God with all our heart, mind and soul”, is not to disappear in some non-corporeal, misty union, but to keep the Divine as our central reference point, and be transformed by the experience, transfused with it as we go about our business with the world and other people.

[15] Saying hineni ‘here I am’, becoming present, and making ourselves available (for example in prayer, meditation, or honest self-reflection), can propel us to right action in the world. Conversely, the ‘hineni moment’ that the Jewish philosopher Emanuel Levinas described (‘Otherwise than Being, or Beyond Essence’, 1974), when we dare to ‘show up’ fully to another person, their neediness and suffering, is simultaneously the most human and most transcendent act we can perform – a moment of revelation both in terms of me revealing me, and in terms of experiencing revelation. (Also see commentary on ‘hineni’ in Shema (2): Love and Follow)