Music and recording © Alexander Massey 19 May 2016

BUY the sheet music (2 vces & pno) – $6.75 (3 copies @ $2.25)

The sheet music is also available as part of ‘Five Sacred Chants’.

There is a shorter introductory article about the music and meaning of this chant here.

“You have all been shown what is good, and what God seeks from you.

Do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8)

[See the Hebrew original, and other translations, at the end of this article]

I love this text. ‘Do justice’ – Yes, do the right thing, make the world fairer. ‘Love kindness’ – this is an important counterbalance. Justice can sometimes be over-exacting, too severe, and lack compassion. Together, justice and kindness make a healthy and wise combination. ‘Walk humbly’ – when we walk, we are not ‘spineless’, but hold our head up with confidence, and we balance this with being humble and avoiding self-importance. ‘With your God’ – staying close to God, and nourishing that relationship, and our God-awareness are crucial to the good life. The chant includes the first half of the verse as well; this expresses our agathotropic nature (inclination to seek and grow toward goodness), and God’s invitation, command, and fervent hope that we do so. This verse from Micah is universal in its humanity. It is a sentiment that can transcend Judaism, and be meaningful amongst any group of people, whether they have a faith tradition or none.

For every piece I compose, I also write a commentary. This is because I believe it is important to make as deep a connection as possible to the intention of the words, and how the words might guide our hearts and our actions. This process of studying the text also helps me feel my way to what music to compose. Jewish methods of scriptural study place great importance on what Hebrew words were chosen by the writers, and the relationships between the different Biblical instances where they occur. My own commentary reflects this tradition.

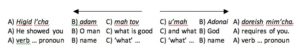

Higid literally means to reveal, explain or tell. We have in Jewish tradition the agadah, which is the rich treasure house of (sometimes highly imaginative) stories to be found in the Talmud (commentary on the Tanach[1], the Jewish Bible); we also have the Haggadah, the centuries-old book (literally, the ‘telling’) that contains the stories and liturgy for Pesach (the Passover rituals) in many variations. So the word higid is not really about God ‘telling’ us what to do, but revealing wisdom through stories, and through giving us a mind that can interpret and have insight. I have translated higid for the song lyric as ‘shown’, suggesting that we are informed through instruction, story and the lived examples of others – as well as, perhaps, through empathy for other people and the web of human life. We do not grow up in an amoral world, but in a world where immorality and morality play out in front of us, and vie for our favour. But the title of this piece ‘You have all been shown’, is a strong reminder that we cannot pretend that we have no sense of right and wrong, or no responsibility for our choices.

Adam, meaning ‘man’ or ‘mortal’ is derived from adamah ‘earth’, which is in turn derived from dom the red colour of the earth; adam could therefore be translated, literally, as ‘earthling’ (or ‘human’, which is possibly linked to the Latin humus, meaning ‘earth’). In Micah, it is clear that historically the Israelites are being addressed. But the word that is used – adam – is the name given to the first human being. The Judaeo-Christian myth of Genesis asserts that all humans are of one family. Adam could be read, therefore, as meaning all of us, hence the translation for this lyric – ‘You have all been shown’.

Doreish is usually translated in the Micah quotation as ‘require’; but doreish is often used to mean ‘seek out’. In this passage from Micah, I imagine God not to be ‘requiring’, but asking, and thereby offering a non-coerced choice. God is searching out our better nature; and for us to know good and do what is good, we must seek deeply within ourselves. The second part of the line may not be a question (‘what does god require of you?’, as suggested by the first two translations), but simply a continuation of the first part: ‘you have been shown … what God seeks from you.’ To know the answer to this requires us to look and listen deeply beyond and within ourselves.

Mishpat represents the whole process of defining laws (legislative), passing judgment (judicial), and carrying out the judgement to punish or release (executive). By extension, for the ordinary citizen going about their personal and professional life, it could also mean to clarify principles of right action, to make decisions based on those, and to follow through on them. It is not enough to think about or decide what is right – integrity means taking a stand, holding a boundary, and doing (asot) what is right. Judaism is not so much a set of beliefs or attitudes, as a way of living – a tradition of embodied values, ideas in action.

In Jewish thought and text, mishpat and chesed (justice and mercy) are often paired. For example, in Hosea 2:21-22 God promises to relate to Israel with these attributes; and these words form a morning prayer for many Jews, committing their minds and actions to these principles. In the Midrash Rabbah (assorted texts collected over eight centuries), mishpat and chesed are often referred to by close alternatives: din and rachamim. “Said the Holy One, blessed be He: ‘If I create the world on the basis of mercy (rachamim) alone, its sins will be great; on the basis of judgment (din) alone, the world cannot exist. Hence I will create it on the basis of judgment (din) and of mercy (rachamim), and may it then stand!’” (Gen. Rabbah 12:15) We derive from this that human society can function only when these qualities are balanced in the right proportion.

Chesed does not have a neat equivalent in English, and has been variously translated over the centuries as ‘mercy’, ‘grace’, or ‘loving-kindness’ (the latter coined by Miles Coverdale in his 1535 translation of the Bible). Chesed is God’s undeserved love and mercy (eleos in the Septuagint[2], misericordia in the Vulgate[3]) towards a person or people. As in the Hosea example, chesed is almost always used in the context of a covenantal relationship; chesed is persistent, loyal, committed, dependable. The word is used to express obligations of love through deep bonds of mutual responsibility. Not only is God’s chesed towards humanity central to the relationship, but doing g’milut chasidim ‘acts of loving-kindness’ is a core principle of Jewish life of how people should behave towards each other. The word ‘kindness’ is not often used to translate chesed, perhaps because being ‘kind’ is not always seen as requiring very much effort or commitment. But I have chosen to use the word ‘kindness’ in this translation because it is a word that has unexpected depth. The word ‘kind’ is etymologically related to ‘king’. A king (or judge) has great power, but can choose to use this power benignly and generously. To ‘love kindness’ (ahavat chesed), is to act generously, applying one’s own wealth, learning, insight, skills, and good fortune for the benefit of others.

The word ‘kind’ is also etymologically related to ‘kin’. Kindness is what we do for another person because of our empathy and bond of humanity – our ‘kinship’ – with that other person. English translations of the story of Ruth make this connection. Naomi (Ruth’s mother-in-law) draws attention to Ruth’s kindness to her, and wishes God’s kindness towards Ruth (Ruth 1:8). The connection is even more explicit in the description of Boaz: “And Naomi said to her daughter-in-law: ‘Blessed be he by the Lord, who has not abandoned his kindness to the living and to the dead.’ And Naomi said to her: ‘The man is nigh of kin unto us, one of our near kinsmen.’” (Ruth 2:20) ‘Nigh of kin’ is the translation of two words, karov lanu, meaning ‘close to us’. ‘near kinsman’ is the translation given for migoaleinu; a more literal translation would be ‘who redeemed us’. It was an important part of the culture to ‘act as kinsman’ towards those in need, acting as their ga’al ‘redeemer’, and rescuing them from adverse circumstances. God does this for the Israelites trapped in Egypt, and Boaz does this for Ruth. The poet-cleric John Donne eloquently expressed the far-reaching implications of our common human bonds:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the main; <…>; any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” John Donne, Meditation XVII, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, 1624[4]

Hatzneia comes from tzana, meaning ‘humble’ or ‘lowly’. In the Jewish discipline of self-development called mussar, humility (normally referred to in Hebrew as anavah) is seen as the most important trait we should try to cultivate. Moses, the foremost prophet, was described with the single virtue of being humble (Num. 12:3). There is only one other place in the Tanach where tzana is mentioned: in Proverbs 11:2, those who demonstrate tzana are described as having wisdom (chochmah). In Jewish thought, the quality of tzana (or anavah) is not self-effacement or self-debasement, but a healthy moderation between that extreme and arrogance. Alan Morinis, in his book on mussar, ‘Everyday Holiness’ (2009) describes this as “No more than my space, no less than my place.” True humility is an honest view of one’s weaknesses and strengths, and absolute equality with every other human being. And we judge ourselves not in relation to others, but in the light of what we have been given, and what we believe our life tasks to be. I like that ‘humble’ is etymologically related to humus, Latin for ‘earth’. (We’re back to adamah and adam, ‘earth’ and ‘earthling’.) We need to stay ‘earthed’, especially when we believe ourselves to be on the side of ‘right’, or, more dangerously when we think we ‘walk with God’, or believe God to be on ‘our’ side.

Lechet comes from halach ‘walk’, and is the same word used for halachah, the vast body of Jewish law developed over many centuries (and continuously even now), that is intended to cover every aspect of life, from bodily functions, what we eat and wear, to how we should behave towards other people, towards the environment, and ultimately towards God. It is the guidance on how to ‘walk’ well through life. We aspire to be like Enoch (Gen. 5:24), Noah (Gen. 6:9) and Abraham (Gen. 17:1), and to ‘walk with God’. Both Noah and Abraham were described as tamim – ‘perfect’, ‘blameless’. Noah was also called an ish tzaddik (‘righteous man’), meaning someone who concerned himself with social justice. Perhaps only those who are blameless in all their words and actions, and devote themselves to social justice could be said to ‘walk with God’. That would mean probably that none of us ever ‘walks with God’, but it could be something to aspire to nevertheless. There is an interesting difference to how Noah and Abraham ‘walked’. Noah was said to walk ‘with’ God, being righteous ‘in his generation’, while Abraham walked ‘before’ God. The early Rabbis concluded that Noah must have been ‘good’ by the standards of just his own time, but that Abraham was a visionary, striving for spiritual betterment and for the improvement of ethical life for future generations. Micah suggests that we walk ‘with’ God; but we could choose to be like Abraham, and aim to raise moral expectations, and refine ethical sensibilities as far as we can.

Jews use many words to address or refer to God. The word used on a particular occasion is chosen because of the needs of the situation and the person. It provides the temporary framework through which the person relates to the Divine (and the situation); focusing awareness on a particular quality can change the situation. In the first line of the Micah text, the word YHVH (Hebrew letters yud-heh-vav-heh) is used. This is the Tetragrammaton, the Hebrew letters to substitute for the unpronounceable ‘name of God’ that Christian texts later transcribed as ‘Yahweh’ or ‘Jehovah’. Instead of trying to pronounce the name, Jews say Adonai. YHVH or Adonai is traditionally understood as referring to the compassionate and merciful aspect of God, associated with ahavah (love) and chesed (kindness/mercy). In the second line of the Micah text, God is referred to as elohim (elohecha meaning ‘your God’). This is the God of judgment (mishpat), discipline and boundaries. Elohim can also mean ‘judges/magistrates’. It is elohim, the strict God, who defines ‘what is good’, but it is Adonai, the Compassionate One who asks rather than orders us to pursue the ‘good’. Micah’s words advise us to find the middle way between mishpat and Elohim on the one hand, and chesed and Adonai on the other; we do this with tzana ‘humility’, which is in itself the wise middle path between an over-inflated ego and inappropriate self-diminishment.

The last word of our text – elohecha – means ‘your God’. Why ‘your God’, and not just ‘God’? In a shared faith tradition, there is a sense of a shared, social constructed theology. At the same time, our sense of what God is to each individual is personal, intimate and unique – and beyond description. The philosopher-theologian Paul Tillich (1886-1965), in his ‘Dynamics of Faith’ (1957) talked of God as being for each person whatever was of “ultimate concern”. His definition allowed for even atheists to have an ‘ultimate concern’. So I imagine and hope that secularists, atheists, agnostics and humanists could also derive something of positive value from Micah’s words: ‘walk humbly with your highest values / what is of ultimate concern to you.’

But has Micah really said anything useful at all? One possible paraphrase is: ‘You know what is good, and what you should do. Be just, be kind, be humble and follow your highest values’. Yet we are left with none of these terms explained. Only by meditating on, and living with, the text, and engaging with life and people and the world, can we learn its meaning.

The music

When Jewish prayers or passages of the Bible are chanted, there is a tradition in many communities of using certain centuries-old musical shapes and scales to do this. These are referred to as nusach or modes. One of those is the Ahavah Rabbah mode, which has been used for this setting of Micah 6:8. It is not the mode that would normally be associated with this passage if one were to chant from the Tanach in a service.

However, I have used Ahavah rabbah for two reasons. First, the words ahavah rabbah mean ‘with great love’, referring to the great love that God has shown in teaching us, and giving us insight. Through using this mode/scale, there is an extra association made both with love, and with receiving wisdom about what is good. (Note that ahavat, a cognate of ahavah, is also in the Micah text.)

Second, the ahavah rabbah mode is often thought of as being the ‘Jewish mode’, and many people think of the music that comes from this scale as sounding ‘Jewish’. But the reality is that Jews have always drawn upon the musical language of the wider culture. The ahavah rabbah mode (which emphasises the third of the scale) originated in a scale from the Arab and Egyptian world with the hijaz maqam (which emphasises the fourth of the scale); this, in turn, has its origins in Greek modes. By the early twentieth century, this mode became popular in Yiddish (Eastern European Jewish) popular song and musical theatre – hence, perhaps, the widespread but mistaken assumption that it was a uniquely Jewish sound. So, the music for this piece, though seemingly particularly ‘Jewish’ in sound for many people, is in fact more universal – in keeping with this text which can be imagined as being addressed not just to Jews, but to Adam, all humanity.

The opening line is in the rhetorical form of a chiasmus, in which the ideas/words are presented in a ‘word mirror’[5]: I wrote the melody to follow a similar structure. It has approximately an arch shape, climbing to almost its highest point in the middle; ‘and what’ (G-F#) is a melodic reversal of ‘what is’ (F#-G); and the word ‘you’ begins and ends this whole line, on the same note (low B).

I wrote the melody to follow a similar structure. It has approximately an arch shape, climbing to almost its highest point in the middle; ‘and what’ (G-F#) is a melodic reversal of ‘what is’ (F#-G); and the word ‘you’ begins and ends this whole line, on the same note (low B).

The melody is shaped to help tell the story of the words. The first musical emphasis is on the word ‘all’; none of us is excluded from this message. The mid-point in the first line highlights the word ‘good’, which is also the longest note in the piece; ‘good’ is the core concept of the text. The first line finishes on the musical ‘root’ (B), the anchor note of the whole piece; the message is, in a sense complete without needing the second line. However, the second line expands the idea of ‘good’. The music for ‘only do justice’ is square and deliberate. ‘Love kindness’ is more lyrical and heart-opening, reaching the highest note of the piece on ‘kindness’; as mentioned earlier, chesed is meant to remind us of our kinship with others, and tip the scales of life towards compassion in what could be an otherwise unbearably harsh world. The falling melody of ‘humbly with your God’ suggests graceful surrender. The music ends with the feeling of a question, something incomplete; the pursuit of ‘good’ never ends.

The two lines of music intertwine, creating strong harmonies, as a symbol of diversity, cooperation, and synergy. I like that when this is sung as a two part round (or in an interfaith context), the ends of the two lines sung together bring the words ‘God’ and ‘you’ to coincide: the human surrenders to be aligned with God – we become One with each other, and with God.

The text

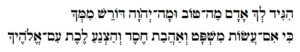

Higid l’cha adam mah tov, u’mah Adonai doreish mim’cha;

Higid l’cha adam mah tov, u’mah Adonai doreish mim’cha;

Ki im asot mishpat, v’ahavat chesed, v’hatzneia lechet, im elohecha.

“He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the LORD require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?” (King James Bible translation, 1611)

“He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, and to love loving mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Jewish Publication Society translation, 2000)

Suggestions for use:

- Begin with a solo voice singing the whole piece, then to encourage others to join in for the second sing-through. Repeating each section gives a chance for listeners (e.g. audience or congregation) to learn the notes the first time, and then copy the second time. The whole piece can become a chant repeated a number of times simply in unison.

- On third and subsequent sing-throughs, the soloist continues to lead the main group, while a second group can join in with the round.

[1] All the transliterations of Hebrew words in this article containing the letters ch are pronounced with a guttural ‘h’, as in the German name ‘Bach’.

[2] 2nd century Greek translation of the Bible

[3] 4th century Latin translation of the Bible

[4] “No man is an iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; <…>; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee….’

[5] Another example of a chiasmus is: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed.” (Gen. 9:6)